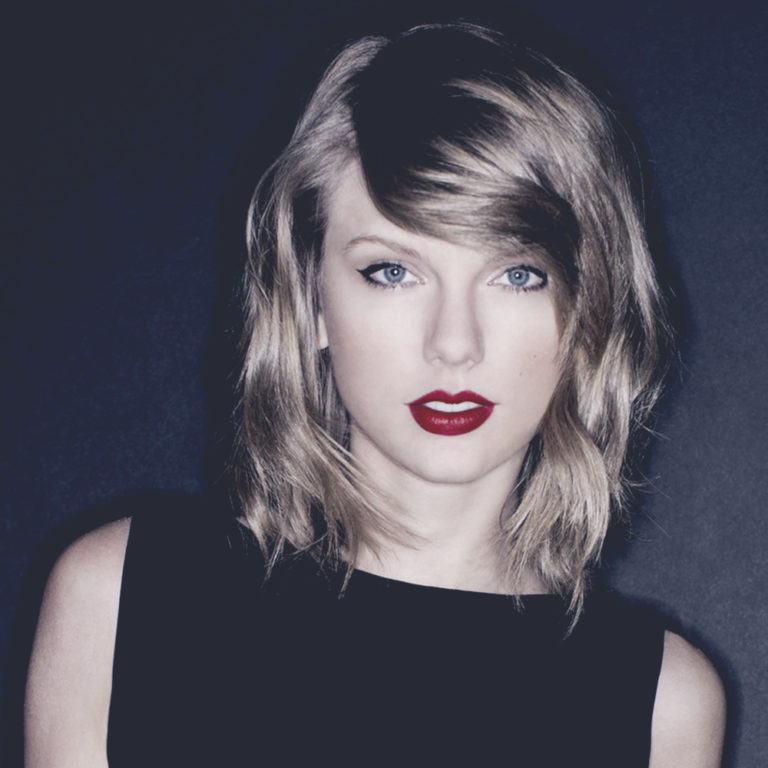

Taylor Swift is having a moment.

Ever since the release of her pop crossover album 1989, the country-phenom turned top-40 dominator has become an inescapable cultural fixture.

The album is one of the most commercially successfully LPs in decades, selling nearly 9 million copies globally, topping charts around the world and garnering hundreds of millions of plays on YouTube. Even user-made mash-ups have become hits.

What makes 1989 different is that beyond making lots of money, it’s a weirdly culturally unifying force.

T-Swift’s “squad” of collaborators includes everyone from Kendrick Lamar—arguably hip-hop’s most important artist—and pop star Ellie Goulding, to Paramore frontwoman Hayley Williams and actress Lena Dunham (all of whom were among the celebrities who appeared in the video for 1989 single “Bad Blood”). Swift claims old fans who love her for her early country work and new ones who buy her pop singles. The album features producing credits for both indie rock darling Jack Antonoff (Steel Train, Fun., Bleachers), as well as pop-music guru Ryan Tedder (the OneRepublic singer who has produced music for pop stars including Beyoncé, Kelly Clarkson, Jordin Sparks, One Direction and Maroon 5).

1989 is the increasingly unique pop album that’s both been almost universally praised by fellow artists and critics and been accessible to even casual music fans.

But there’s something else at play with what Taylor Swift’s appeal says about the church…

The Cultural Moment

1989 is a great album, and its singles are pretty great songs. But with pop music, the music is only a small part of what makes an album. In many respects, pop music is as much about image as artistry. It’s as much about an underlying idea as it is about actual lyrics.

Elvis was iconic only in part because of his music. He represented a shifting cultural mood as much as he did a genre. The Beatles’ music holds up, but so does their style. Michael Jackson was a musical genius, but there are lots of musical geniuses; there’s only one King of Pop. Beyoncé is a hit-maker, but it’s her image of self-empowerment that has helped make her a superstar.

There’s a famous quote from philosopher Joseph de Maistre that says, “Every nation gets the government it deserves.” You could make the same case for music: Every culture gets the pop stars it ultimately deserves. Culture helps create the pop stars it wants to follow.

Pop stars are more than just the sum of their songs; their success is partly due to what their success represents.

Elvis was about the rise of youth culture, and the loosening of Puritan values. The Beatles were about the cultural expansion and the embrace of new ideas. Michael Jackson transcended racial barriers. Beyoncé is a self-made female mogul, who has helped embody the cool confidence of culture shifters. Across any pop music era (the rise of grunge, hip-hop, glam-rock, Motown, etc.), trends are reflective of not only cultural values—but of cultural voids. There’s a tendency for music fans to use artists to help vocalize and embody things they want to see in culture.

Looking at what the pop star of the moment—who, in this case, just happens to be a Nashville singer with a multi-platinum pop album—represents, not only helps show us something about culture’s collective tastes. It can also be a look at the void it’s looking to fill. It’s a void the Church also needs to respond to.

The Swift Appeal

One of the things that has made the rise of Taylor Swift so interesting is just how proactively uninteresting she tends to be—at least in the shock-value, tabloid sort of way. Sure, she writes about personal relationship drama, but it’s always in a veiled, mostly innocent way. She’s more known for squashing beefs than starting them. In the case of a Twitter dustup with Nicki Minaj, she was downright apologetic.

https://twitter.com/taylorswift13/status/624240681750536192?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

The most recent VMAs were a perfect example. In an evening that featured performances, outfits and appearances that repeatedly attempted to out-shock each other, Taylor Swift’s screen-time was mostly tame and gracious.

For better or worse, Taylor Swift is safe. Even though 1989 was a creative risk, it was a highly calculated one. (The campaign surrounding its release literally involved her move from Nashville to New York.) Whether carefully cultivated or authentic (or both), Taylor Swift’s image is predicated on her niceness to fans, her love of “squad” friendliness, her innocent romances and her graciousness toward other artists.

It’s a brand our culture has embraced, because it’s one our culture wanted.

What the Church Can Learn

Church planters, theologians and evangelists are constantly looking for ways to “reach” culture and relate to the needs of the collective masses. The appeal of Taylor Swift provides a look at just that.

And what makes that kind of image—a safe, friendly, gracious one—so noteworthy is that it seems to directly contradict the way so many Christians are perceived (at least in the media). A look at modern headlines involving Christians mostly focus on the most divisive issues—from anti-gay marriage activists and undercover stings to infighting pastors, social media gangs playing theology police and scandal-ridden leaders. The message that is often perpetuated flies in the face of what culture seems to be gravitating toward.

In a time when so many Christians and Christian leaders take a defensive, combative tone (especially in this political season), culture finds its next pop star in a girl-next-door who seems to have little interest in salaciousness, edginess or picking fights. Swift’s image is about uniting—stylistically and squad-listically—not dividing.

Scripture teaches that Christians should observe certain moral rules and followers of Christ should stand up for the victims of injustice. But if the collective image of the Church becomes more known for what we’re against than what we’re for, we risk isolating a culture that’s interested in unity. There are certainly causes that are worth fighting for and evils that need to be exposed. But there are also people who need to know what it’s like to be loved despite their failings, to get a second chance and experience what grace looks like.

Just like late-night TV’s revolution shows how culture’s taste for cynicism is souring, Taylor Swift’s massive appeal is evidence that popular culture is looking for a unifying tone to counter the absence of just plain niceness in our discourse.

In some circles, there’s been a refrain that Jesus wasn’t overly concerned with being “nice.” It’s true that there’s a difference between niceness and love, but that doesn’t mean they are mutually exclusive. Yes, Jesus preached truth—even when the message was difficult for some people to hear. But He also carried Himself in a way that drew large crowds, endeared Himself to masses and that made people want to leave everything behind and follow Him. He treated people with dignity and respect. He didn’t try to further divide people and their enemies. He tried to bring them together.

The rise of a pop star like Taylor Swift shows that at least some part of culture finds the idea of unity and niceness appealing in times when so many things are so divided.

Haters are always gonna hate, but the Church shouldn’t be among them.

relevantmagazine.com